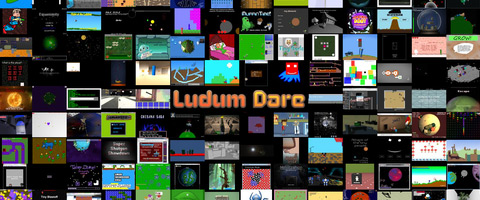

Ludum Dare #23 – The Report

Welcome, dear international readership!

Please allow me to introduce myself: I’m Sebastian, I’ve studied “Cultural Sciences and Aesthetic Practice” (2008-2011 in Hildesheim), right now I’m studying “Staging of Arts and Media” (in Hildesheim). Having a preference for the digital game, game studies quickly became my research area. They’re also my reason for writing papers about computer games as well as articles for the German TITEL-Magazin.

For Superlevel, I went on a quest to test all 1.402 games of the Ludum Dare #23 – yes, every single one. I’d like to give you an overview over particularly innovative gameplay, wonderful ideas and exquisite digital entertainment. Have fun!

It all started back in April of 2002 when Geoff Howland established the Ludum Dare – a friendly and productive competition between hundreds of programmers around the world. Each participant develops a game set to a common theme (this year’s was Tiny World). The developers have serious time pressure, though: In the Jam Category, teams of developers must create a game in 72 hours, while in the Competition (Compo) Category, games have to be created by a single person in only 48 hours. This year’s result: 1.402 games.

The atmosphere of minimalism

Playing this year’s submissions, I found that the choices of protagonists and scenarios were very distinctive. You often play as a mini-, micro- or even nano-organism. Ants and spiders, germs and cells, individual pixels, nano robots or quark particles. The exact opposite was a popular approach as well: Playing as a giant or a big planet surrounded by the infinity of space naturally makes you feel small just as well. But it’s not just the fundamental decision of setting that is influenced by the slogan; a disposition towards graphical minimalism is clearly recognizable, too.

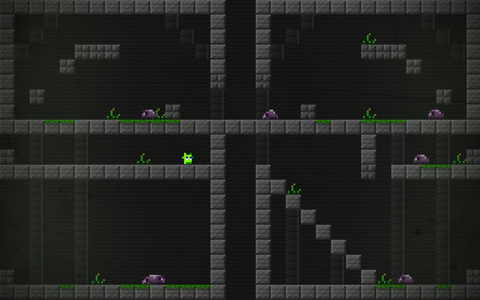

(Download Incomplete)

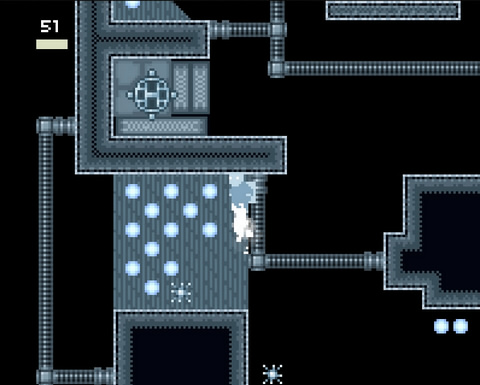

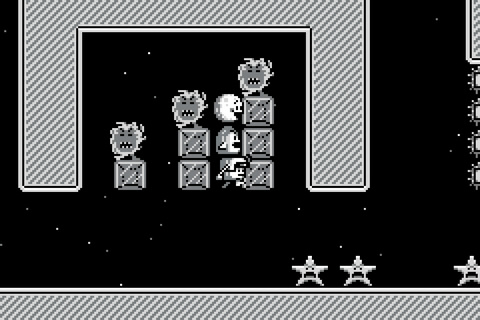

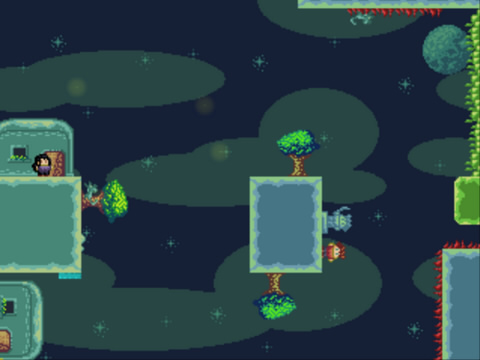

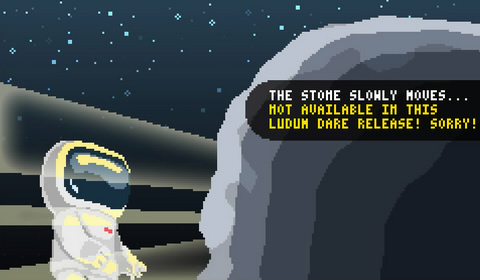

The pixel and its retro aesthetics are a common element of the games, even if they’re contradicting the respective genre. Pixelated science-fiction games are not a rarity: Download Incomplete lets you play the ghost in the machine. Equipped with your trusty jetpack, you have to find the last missing bytes of a download. The puzzle platformer Millinaut refines this approach even further by using anthropomorphized enemies like angry-looking stars or aggressive suns. It reminds me of the good old days in school, white GameBoy in hand.

This feeling is intensified by excellent pixel graphics with shades of black, white and gray as well as the very appropriate bleep-bloop music. Furthermore, Millinaut offers great puzzle design. You’re playing a group made up of an astronaut, a rocket and a moon. The three are stacked on top of each other, with the astronaut being the bottom part, making the whole group jump and run. Both the rocket and the moon can be fixed in mid-air as platforms, but it’s possible to deploy them on command, too. The rocket can fly, the moon falls. This lets you defeat enemies or gain access to unexplored areas.

(Millinaut)

What makes Millinaut special is its fragmentation of the essential abilities of movement and fighting. Even the fighting ability itself is fragmented through the rocket and the moon. A common (and trite) convention was broken: The union of all essential skills in one single character. All of this leads to a particular aesthetic, an atmosphere of minimalism. We become aware of a pool of skills, stripped down to their basic elements. But it gets even more interesting when the game’s narration is detached from the game itself.

A great example for this is Acari Love. You support Bernardo the mite in a shooting carnage against other, bigger monsters. The music is fast and keeps the pressure up. It’s minimalism on two levels: The player directs Bernardo with the mouse and drops the occasional bomb with a left click — you don’t have to worry about shooting, Bernardo does that automatically. This limits the gameplay to mouse control. The other, much more important feature is the break of the game within itself. Following each victory, the music slows down abruptly. Suddenly, it’s quiet. The player sees nothing but a white text on a black screen. And then Bernardo tells his tragic story about the death of his sister and his fight for his only love.

The story may seem idiotic and absurd (keep in mind that he’s just a mite in a mattress), but really it doesn’t matter at that precise moment. Developer SergioAwoke knows how to properly use language. Instead of writing something like „Oh damn, these stupid humans killed my sis with an anti-mite-spray! >:(“, Bernardo only says: „My sister died last night.“ Acari Love seriously touched my heart, even more than most current role-playing games. And that’s no easy thing to do, believe me.

Reduction of game mechanics and its added value

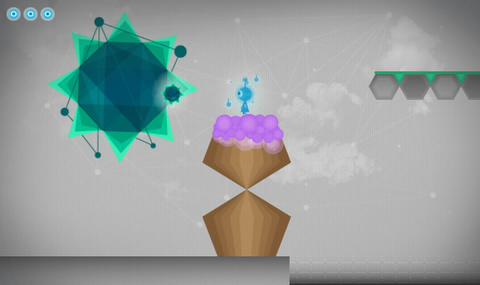

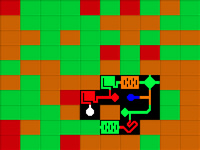

(Pow! Pow! Pow!)

Ludum Dare #23 turned out to be a site of pilgrimage for programmers affected by minimalism (both on a visual as well as an thematic level). There’s a certain suspense when the whole game mechanic is reduced to one active opportunity for action — but it’s even more powerful if that action has several functions.

Let’s take a look at the little blue alien in Pow! Pow! Pow!: His energy projectiles not only defeat enemies, but they also influence the game world itself. For example, you’re able to shrink down enormous metal spikes or use environmental elements — such as compositions of huge triangles with purple bubble-frosting standing all around –- to sling yourself and overcome obstacles and gorges. It’s just one skill, but it’s got three core functions – not too bad, is it?

The game gravity is minimalist in a similar fashion: Playing as a yellow cube on a tiny island floating above deadly lava, you have to shoot red cubes that fall from the sky. But the thing is: Red cubes don’t vanish, they turn into gray cubes and start occupying the small island of your yellow cube. If you don’t shove the additional weight over the edges, the island will sink right into the red sea of death.

The game gravity is minimalist in a similar fashion: Playing as a yellow cube on a tiny island floating above deadly lava, you have to shoot red cubes that fall from the sky. But the thing is: Red cubes don’t vanish, they turn into gray cubes and start occupying the small island of your yellow cube. If you don’t shove the additional weight over the edges, the island will sink right into the red sea of death.

The reduction of game mechanics leads to additional value for players as soon as multiple factors influencing each other need to be considered. New challenges appear at the same time, only to be solved by one single action.

Super Meat Boy’s new garments

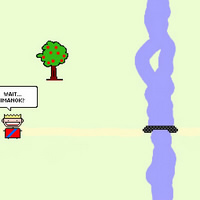

Another ongoing theme is the hommage to earlier, iconic games and the gaming culture in general. The point’n’click-adventure subAtomic shares not only the look of its ancestors from the 90s, but also their humor. Another example is the short ‘adventure’ Tiny Quest, which can be solved via knowledge of one pop-culturally relevant cheat co… Nope, I won’t tell you. There’s a hint in the image on the left. But psssst… Don’t tell anyone!

Regarding rip-offs (but with their own perks) of Super Meat Boy, there’s two that stick out immediately. One is Muffin Time!, in which you perform some wall-jumping in an inceptionesque world. An alien, who is obsessed with muffins, stole one of them on a spaceship and thus activated the ship’s self-destruction mechanism. To deactivate it, the alien fights robots and other safety measures. Each of them is made out of a number of levels, though. Seems like we can file that one under MuffInception.

Fortunately, Superpixel was much more enjoyable. Nearly everything here reminds me of Super Meat Boy: The form of the protagonist (well, it’s a pixel…), the ‘Super’ title, deadly spinning objects and – of course – the wall-jumping at the very core of the gameplay. But it’s much more than a simple copy of a superb indie game. Its programmer lectvs poured a huge amount of love into the detailed level design: In just 48 hours, he created an easy and a hard level of difficulty for all of the 21 stages. Actually, the easy mode itself is a considerable challenge and the hard mode is… well, very very very hard. It’s frustrating and fun at the same time –- just like the original.

![]()

(Superpixel)

Another theme shared by many submissions is the relationship to other individuals and the consequences of them for your own life. There’s games where love is embedded in the narrative arc. Even the choice of the survival-genre can be explained by through loyalty to a higher power. Other games discuss the relationship between players and game designers. But two of my top favorites contextualize the abscence of relationships. Let me try and explain it like this: A limited surface (tiny world, remember?) causes closeness between its inhabitants. If that closeness doesn’t exist, we miss it even more.

Adventures about the lack of relationships

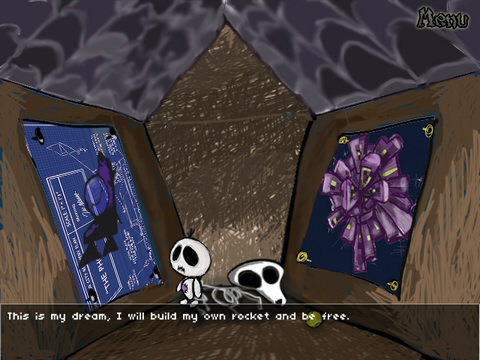

(Tiny Journey)

I was impressed by two adventures in particular. Although they both have completely different gameplay, graphics and atmosphere, their protagonists share a lack of relationships. The bizarre/tragicomical point’n’click-adventure Tiny Journey tells the Jack Skellington-like story of a lonely kid without a name. There’s only one day a year when the little guy can leave his room: On his birthday. In his tiny chamber, he’s drawing blueprints for a rocket. As you begin to play, you see him dreaming of freedom, waking up, changing from depressed to encouraged. He decides to escape the awful place he’s stuck in, even without the permission of his parents. Going outside, he notices that nobody else is there. The player helps the poor guy search the missing rocket parts. The whole time playing, we never see anybody else. There’s just him and his dead dog (which we see only once). His destiny is heartbreaking. You’ll leave this game with mixed feelings, but you will certainly be aware that its creators did amazing work.

(Ancestor’s Sword)

The other splendid achievement is the platform adventure Ancestor’s Sword. Here you explore a world filled with friendship, lovely and calm. There are children playing, lovers, peaceful people knowing that there’s nothing evil in the world. There’s cute little cats, too. You control the bored grandson of the local hero (who made the world safe in the first place). The grandson wants to become an adventurer and sets out in search for his grandfather’s blade. Derived from the central idea of VVVVVV, Ancestor’s Sword lets the player flip gravity with a single keystroke and thus move from platform to platform, from floor to ceiling. as long as he is near enough to make the jump. To access new areas you have to find a watering can and use it to grow giant plants, climbing them to journey onwards/upwards/downwards. The spatial riddles are complicated further by nasty thorns on the platforms, which restore the ‘hero’ to his previous position whenever he touches them. According to developer JaJ, there are two endings. I merely found the most obvious one. Still, it should become clear what I mean by lack of relationships. Ever handed a bored youngster a sharp blade? No? Do it! You’ll see what I’m saying. My mad giggling got stuck in my throat for a while, until I had to laugh again. A marvelous feeling. But there are even more fantastic games grappling with love and longing. Is there anything better than to commit oneself, heart and soul and all, to another person?

The melancholy of pixel-love

(Pretentious Game)

The platformer Pretentious Game uses this theme in a very clever way. The sometimes more, sometimes less cryptic game instructions are written as a love poem. A gentle piano score won’t let you avoid the romantic atmosphere. Although you only play a single love-struck pixel, everything seems to fit this amusing, emotional pleasure. Furthermore, Pretentious Game teaches us a lesson about the format of the digital game as well as about life itself. I don’t want to spoil it right now – experience it for yourself.

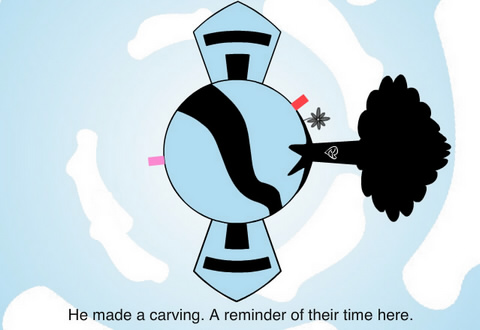

Tiny Vessels on the other hand isn’t really a game in the traditional sense at all, rather a melancholic story about exploration. As a small pixel block, you wander around the perfectly circular world. You carve a heart into a tree, you leave a note at the house of your beloved, you build a fence for her and pick up her favorite flower as a present. All the while, you try to follow her, but she moves simultaneously to you and seems to distance herself. Quickly, it becomes apparent that this was the past, because you now control the pink block and your tiny world is in ruins. The tree with the heart becomes a grave, the house is ruined, the flower gone, only the fence remains. The lover is dead. I shuddered, briefly. I haven’t thought about that before. Surely, something must’ve gone wrong. I noticed it, but I couldn’t put my finger on it.

(Tiny Vessels)

Both Pretentious Game and Tiny Vessels tell us — each in their own way — a simple, yet important message: Carpe diem. It doesn’t take fancy graphics in high quality to tell an emotional story. It requires aesthetics. The atmosphere of minimalism is used to foster identification. It’s not a human shape of a character or its ingenious personality with an elaborate backstory that makes a game a touching work; it’s the atmosphere, the mood. Love is a trans-cultural phenomenon. Nearly anyone can connect: it’s love that connects us to our families, to our best friends, our partners. There is always a certain someone who must not be absent in your life. Due to the universality of love, these usually abstract pixel heaps can be filled with life by players. The atmosphere of minimalism becomes a strategy, an invitation for empathy.

The survival genre and the higher power

If that’s too too smarmy for you, there’s a variety of different genres offered by Ludum Dare #23, such as in the survival game The Underground Court. Here you take over the role of the last remained insect servant beside its queen. She must be fed to secure the continued existence of your colony, which forces you to move into the outside world to scavenge for food. If you don’t, the queen will die, so you pick up fruits of trees, search dumps for food — you can even snatch cake from a neighbor’s garden. Should you carry too much food, you’ll slow down, though. This is dangerous: The queen can die of hunger if you don’t move quickly enough or you can be ripped apart by stray cats. Without the implied hierarchy of worker and queen, assigning you a value based on the insect’s societal rank, this game would just be ridiculous. The simple act of carrying objects from place A to place B offers no motivation to play at all if it isn’t contextualized.

Meta: Do it yourself!

This leads me to a question: Is a game designer the higher power superior to the gamer? Some interesting games make this relationship the subject of discussion. Level editors are a wonderful example. They turn gamers into game makers themselves. This is why I like the basic idea of the puzzle shooter Nineties Holywood Hacker so much: On a 10×10 field, you create a circuitry by linking up a start and an end element with pseudo-technical symbols. When you’re done, you have to get a tiny aggressive robot through your self-made maze fighting anti-virus programs along the way. The execution is a bit boring and inconvenient, but I was amused by the great idea at the core.

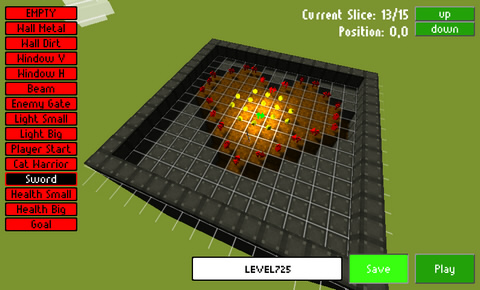

Another great editor is the minecraftesque dungeon editor Wunderworld. With its simple handling it’s fantastically user-friendly. You can choose how many fields long, wide or deep your dungeon should be, whether there are destroyable dirt- or impenetrable metal-walls, where your starting point is, if and how many enemies (there’s kittens again — warrior kittens, rawr!) shall be fighting against you, and much more. Wunderworld offers huge freedom to the player; kudos to the development team Ratking for making the relationship between the player and the designer interchangeable! By the way, I created a tiny dungeon for you guys: It has a big old heart of meta.

(Wunderworld)

To infinity and beyond?

Of course there are still some borders between players and designers. Borders are important, as they define the game environment and its system of rules. In some games, they become a central part of the gameplay or the narration. A great example is the platformer Another Kind of World. You need to kill every enemy with a bomb to find a hidden door, which leads you to the next level. Admittedly, that sounds like an average game, but there’s a twist: The horizontal and vertical borders are connected — like portals. The transformation of the visual 2D borders (the player’s point of view) to spatial non-borders (the character’s point of view) makes the amusing level design of Another Kind of World possible. It enables a bigger scope of action: Across detours, you throw bombs on your enemies. You need to pay great attention as well, because it’s kind of unusual to imagine a room without borders. You’ll often run into the levels’ holes and jump straight up into enemies.

(Another Kind of World)

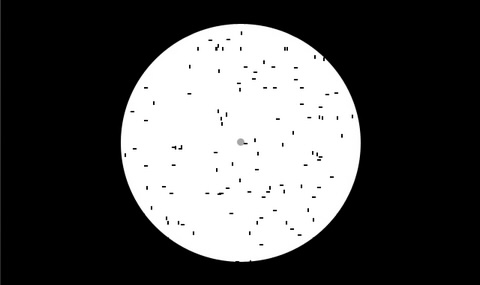

The totally marvelous Microscopia uses the model of a room without borders as well. Here, your goal is to lead a little black line into the center of the white round world. This time, the usage of a boundless room doesn’t lead to a extension of the playing strategy like in Another Kind of World, because you aren’t the only line in the tiny world. There are dozens of them, moving like crazy, even through visual borders. In later levels, the objects adapt to the speed of your movement, sometimes moving in the same direction. The game wouldn’t be playable with determined spatial borders at all, because you’d be able just move into a corner to focus on your character. Its creator, azurenimbus, managed to work around this with the simple extension of the room expand a simple objective — reaching a central point — to a nearly impossible enterprise. Microscopia is a brilliant example of conceptual simplicity.

(Microscopia)

Spatiality of the narration and narrative room structure

Conventions of a genre may be regarded as borders just as well. You can make them visible by a simple change of roles, such as in the ‘Capitalism simulator’ Recettear: An Item Shop’s Tale, which lets you play a young shop owner instead of the brave hero. My Little Dungeon does something similar: Instead of fighting monsters using a sword and shield, you must support the hero by building an underground passage to the monstrous boss. Meanwhile, the AI-controlled adventurer fights against slimes and evil knights, loses life points, gains experience, and even becomes hungry. The hero has to travel a way that you built out of three types of chambers: One chamber with weak enemies, one with stronger enemies and one monsterless cave for relaxation. The choice of rooms has to be balanced to make the adventurer vital and strong enough when it’s time to fight the final enemy. My Little Dungeon centers the structure of a typical role-playing game: a strictly bordered, linear game with a balanced difficulty level can lead to an optical training curve. The miniature rooms are a metaphor for the basic structure of a whole genre, the story of a role-playing game can be told in as much as a small, bordered environment.

(My Little Dungeon)

So we see, borders aren’t something we should categorically define as bad. They don’t automatically result in boring game design. IÄTI, for example, is an inspiring game because of its borders. With the encrypted help of a lyrical myth — a symbiosis of a Finnish creation myth and the national epos Kalevala — you build up the level. The myth tells you the game mechanisms:

„From the eggshells of a bird the world was born.

Earth, water, grass and man.

But be careful, for water drowns him, earth buries him

and ill spirits will surely be his undoing.

Grass to Man. Water to Grass. Grass to Shrub. Sing the old chants.

Grass to tent. Man to tree. Water to boat. Sing the old chants.“

You control a flying bird and let it lay eggs in different colors, each creating something new: Green eggs produce grass, orange eggs create humans and so on. Should a green egg fall down on a human, they will become a tent. It’s the mix of the elements that lets players become storytellers of the myth.

(IÄTI)

Boundaries as the basics of a game

Sometimes borders are simply entertaining. In Spaceship In The Sky With Colors you fly a spaceship through a four/five-colored galaxy. Your fuel consists of the colors blue, yellow, orange and red. If you move through an area, the same-colored fuel gets consumed. This has you switching neatly between the borders to win the game. Boundaries become the basic element of the game.

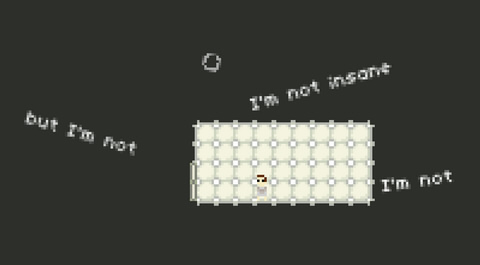

Until now, I’ve only been talking about spatial borders. Asylum starts off in a locked padded room. A schizophrenic talks about the voices in his head, whom he describes as his friends. The doctors try to keep them under control using psychotropic drugs, but the man doesn’t want them. He thinks they’ll summon a monster, so instead he wants to kill it to become a free man. I don’t want to spoil too much, so play it for yourself — it’s really great! The absence of music just makes the story more potent. It’s about a man who gets lost in his own psyche. One part of him, his schizophrenia, is his very own boundary.

(Asylum)

About the essence of a genre

Let’s talk about one concept in particular: a part. To me, it’s a pretty indefinable term. Is a part just a single fragment of a bigger system? Is it possible to disconnect it from its context? There’s a saying that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. But then what does it mean to be a part of something? When people talk about games, they often talk about about discrete parts. There’s graphics, level-design and so on. But could there be something — anything — that makes a game the game it is?

(A Super Mario Summary)

Let’s take a look at Super Mario, the ultimative video game pop icon. To many people, the games about the adventures of the chubby plumber with a gusto for mushrooms are the quintessence of the jump’n’run- and platformerbgenre: Running, jumping, stomping Goombas, collecting coins/points, getting to the finish line. A Super Mario Summary underlines exactly this. It seems to be a copy of Super Mario Bros. – with indie-aesthetics. Both the level design as well as the gameplay are minimal. You’ll recognize the over two and a half decades old game as a representation of the platforming genre itself. Exempted from additional features like the invincibility star or the instant growth spurt by consuming mushrooms, you just play by running, jumping, overcoming obstacles and successfully arriving at the end point. The features may influence your experience with the game, but they’re not its core. They seem to be redundant parts, needed to be removed to identify the essence of a game and a genre.

But what does ‘successfully arriving’ mean, exactly? That a hero doesn’t die? The platformer Crysthurl begs to differ: Here, dying is at the core of the game. You play as a small but very strong creature with a block over its head. You can throw it away, but the block is a unique. For most riddles, one block isn’t enough, so the mini-character must die to reproduce itself with a new block — throwing a block, dying, coming back to life with a new block, over and over again. Crysthurl shows that countable lifes or energy points are not a core element of platformers.

(Crysthurl)

In accordance with the environment

But is there an essence to the digital game itself? Video game theorist Jesper Juul wrote (in an awesome anthology) that a game requires a system of rules. As you start to play, you become a part of that system, because you participate in it. The controls of a game are rules themselves, i.e. in some games you can let your character move to the left or the right only, but he isn’t able to jump, fly or dig. You can’t simply change the environment while playing. Boxed in eases that structure. In addition to controlling the character, you need to literally shake the game environment like a little box in to influence the laws of physics.

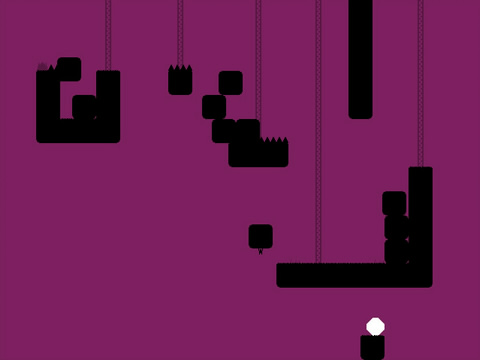

(Inside My Radio)

Inside My Radio, on the other hand, relies on non-controlable room physics. It links the movements of the player character (except for going left or right) to the bass of the background songs. The small green thing can only jump or sprintas long as the player doesn’t sync keystrokes to the background music. That’s pretty unfamiliar, which makes the movement a little clumsy at the beginning. But within a short period of time, it’ll feel pretty natural; the player will literally move in sync with the game.

Me, myself and I

(Memento XII)

To go a step further: What are the essential parts of personality and identity? Which parts are needed to be a human being, a person? The great adventure Memento XII deals with these question. An old man wakes up in a jail cell for the 4380th time. Over the course of twelve years, his whole life has become a routine. He recognizes the three ripped parts of the photo of a woman. He remembers her, her name is Lydia. Suddenly, the cold jail cell transforms into a bright, warm living room, in which he finds various other memorabilia about his past. They’re not just relevant to the scenario of Memento XII; they also show that no human identity can exist without them. Without the knowledge of the past we can neither tell who we are nor what we do and why we do it. I don’t want to spoil the ending of Memento XII, but it mediates this idea to the player in a wonderfully tragic way.

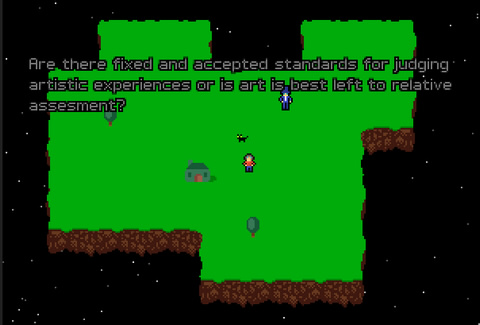

(Flyspeck)

I already had 800 games behind me when I played the short adventure Flyspeck and suddenly asked myself why exactly I was writing this report. In Flyspeck, there’s a kitten named Kitteh appearing as a secondary character. It helped me find an answer by asking existential questions like this one: “Are there fixed and accepted standards for judging artistic experiences or is art best left to relative assessment?” As I read that, I had to smile. Indeed, these questions could work as pointers for reviewing digital games for some people.

Not for me, though. This article is not a search for some fixed and accepted standards for judging games; it’s extremely subjective. I’m trying to transform my most important experiences with the Ludum Dare #23 games into text and share it with you. This is about the liveliness of the games medium, of its agility. Digital games are not just entertainment products. They can touch us, physically and emotionally, they can mediate knowledge about the structure of systems and events, they can develop and extend our consciousness. We can’t accept that they can be rated with some markers like five stars for graphics, four for sound and gameplay. Those single parts don’t add up to the sum of the whole thing. This is why I’m writing this thing. This became a part of me. But what happens as soon as it ends? I’ll certainly have more time for other things — more time for myself, too — but for a short while I will definitely be feeling kind of empty. That’s pretty normal, I guess. For the last eight or nine days I spent around 16 hours daily testing games. And then there’s… nothing.

Emptiness

(The Dream Sequencer)

The point’n’click adventure The Dream Sequencer tells a harsh story about emptiness. You control an astronaut, familiar with the galaxy and his spaceship. But he’s longing for a planet named Earth. He wishes to witness a real day, a real night. However, he begins his daily routine and something goes horribly wrong. Suddenly, he’s standing in a strange room with weird messages on the walls, where he sees shadows come to life. He wakes up yet again. Everything feels like a déjà vu, but now he tells you about his never before mentioned life as a married farmer. In the end, the mystery is solved: He never was an astronaut in the first place. He also was neither a farmer, nor a human. And he certainly wasn’t a living thing. He’s part of ‘the void’, a manifestation of emptiness. His master tells him that he’s been dreaming again. He gets obsessed with each of these dreams and thinks that they are real — but that’s impossible, because he’s nothing. All of this seems to happen again and again. He’s troubled with his non-existence, his literal nothingness. The player is told a subject-specific, superficial yet thrilling dialogue about existentialism.

(Obsolescence)

The exploration game Obsolescence is another one about emptiness, but more in an apocalyptical way rather than a metaphysical one. What happens to mankind when Earth loses all of its resources? The player fires probes to find a new home. If you’re lucky, the scenario changes to the new planet with a filled resource bar, sinking over time. Mankind starts to cut down all trees and to build skyscrapers. If your resources are completely used up, and you can’t find a new planet — Game Over. There will be no planet, no humans, no life at all. In this game, emptiness is your motivation to continue playing. Obsolescence has a moral message. It’s an appeal for sustainable thinking and acting. Only mankind itself can protect the planet from emptiness.

Mind the gap

(Scape)

Emptiness can turn into something positive, because it is a reason to act. In the puzzle game Scape, the subject of nothingness is present as you fight against blank spaces in a tiny world. You’re forced to plant a tree into each of its fields. Do it carefully, because two steps later, the trees are fully grown, which could lead to you blocking your own path. Every step must be well-considered. Another element that needs to be kept in mind at the same time are brown, theoretically not plantable fields — they only become plantable when there’s a fully grown tree right beside them. The level design of programmer intmain was a blast and I sincerely hope he’ll further tap its potential, even after Ludum Dare #23. He sure knows how to use emptiness as a creative and enjoyable part of gameplay.

Emptiness itself is not that much of a new theme, actually. Just remember the 1972 published video game classic Pong. Here, the omnipresent black background is a screen-filling, giant void, but because of its very nature, the players can focus on the white game elements: Their paddle lines and the pixel ball. The emptiness is what lets the player focus on what’s important. MacroPong exaggerates that principle with its ludicrously big background and small striking surfaces. The ludic core of the game gets visualized by the lack of decorative and unnecessary elements, by the emptiness itself.

(MacroPong)

„I’m So Meta, Even This Acronym“

The meta-comment Wander, which pretends to be a game, uses that knowledge to offer a special moment of enlightenment. The title screen promises an „immersive interactive experience“, but then error messages about hardware requirements (i.e. the weak graphics card of the player) appear. Wanders shows nothing but a pixelated mini map. You can recognize a castle, a forest, a big city, the ocean and a river, which passes through the whole area: It could have been such an amazing experience, if only the hardware would comply to the game’s needs. But is the gaming experience really coupled to technology that much? What distinguishes my SNES/PSOne generation from the C64 veterans or the Xbox360/PS3/Nintendo 3DS youngsters of today? It’s true, the electronics and the respective graphics changed, but the basic requirement of playing never changed. We always just needed one single ability to play, regardless of whether we played with Lego bricks, puppets, plushies or with digital games. Which one might it be? The developer Dramble reveals this little secret in the following elegant and brilliant expression:

(Wander)

Constant coincidence as restrictive practice

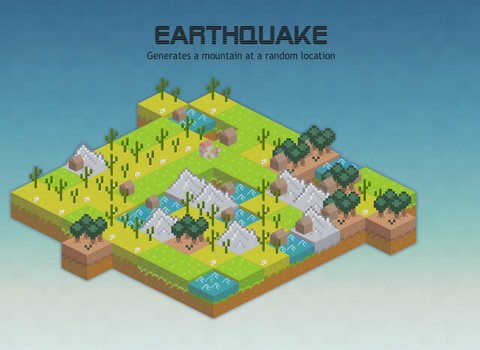

(Tinysasters)

But what happens when your imagination — and by that, your gaming experience — is limited from beyond your control, for example through constant coincidence? In the ostensible construction simulation Tinysasters, everything could be so easy. Its 8×8 field is a tiny world with surfaces of grass, forests, water, mountains and deserts. Your aim is to build a level 4 shrine. To receive the required resources, you need to construct other buildings like mines (for stones) or small towns (for tools). But you must be careful, because even those can’t be built out of nothing; that’s why you have got a limited starting capital of resources. So you’re forced to figure out how to establish an optimal, profitable system. Suddenly, the incredible happens — a natural disaster. Out of the blue, a mountain arises and kills off any other fields in its row. Another variety of uncontrollable catastrophe is the drought, which transforms lush meadows into an unusuable desert. These natural disasters happen in a determined time interval (somewhere between 15 and 40 seconds, depending on the difficulty level), but in random order: Sometimes there’s two earthquakes in a row, sometimes a flood, maybe another earthquake, a drought, and your whole strategy turns out to be waste of time. The liberated feeling of playing the first minute of the game becomes a test of reaction time, at least in the highest difficulty. The permanent presence of the coincidence offers the players a challenge of problem solving and quick adaptability.

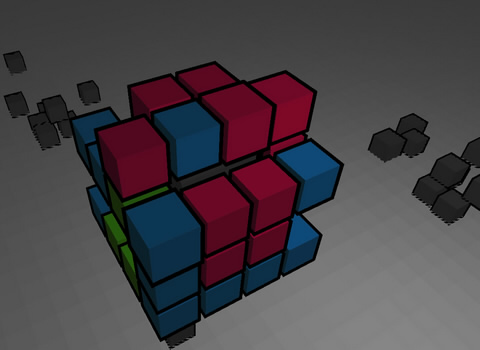

(Serendipity with Cubes)

In a similar fashion to Tinysasters, while in a more subtle way, the mechanic of coincidence is implemented in the puzzle game Serendipity with Cubes. A 3D cube can be viewed from all perspectives. Each round, two random components of the cube begin to pulse, indicating the start and end points of a path the player has to create. The path from A to B must consist of isochromatic components. Along the way, each component can be exchanged with any other. If that connection is established, every path component is removed from the main cube. The final goal is to remove every component, but the real highlight of this game is the condition for losing: If only one single component remains unlinked to the others, the game ends. Each and every step must be carefully planned. By the mere implementation of such a simple random generator, a limitation in playing occurs — but along with that, there’s an enormous suspense. It’s a very captivating game.

The moment of enlightenment

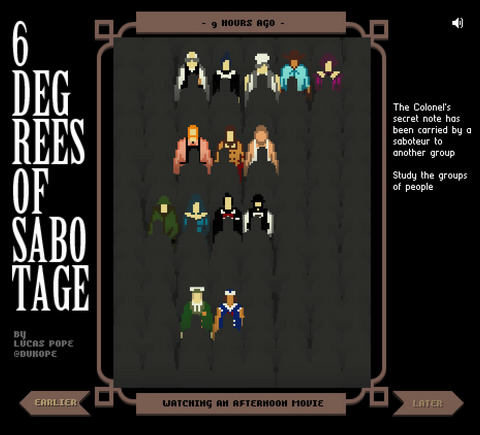

(6 Degrees of Sabotage)

Another interesting employment of coincidence appears in 6 Degrees of Sabotage. It’s a logic game where the player must reconstruct a crime. In the aftermath of a bomb attack, you receive three pieces of information: 1.) The identity of the attacker, 2.) the identity of the constituent, and 3.) that three other people were involved. The group of five is randomly mixed at the beginning of each new game: Sometimes it’s the butcher who executed the attack, sometimes the colonel or the sailor. This reconstruction is exciting because four ambiguous sequences are shown. In the first, the executor meets two other — maybe completely innocent — persons on his or her way to work. In another, you see the constituent in an afternoon cinema movie with three suspects. You need to investigate the footage for information about the relationships of the people. The last act marks the final strike: In a panicky mass of human targets, all guilty suspects need to be killed, each with a single bullet – without hurting the innocent, of course.

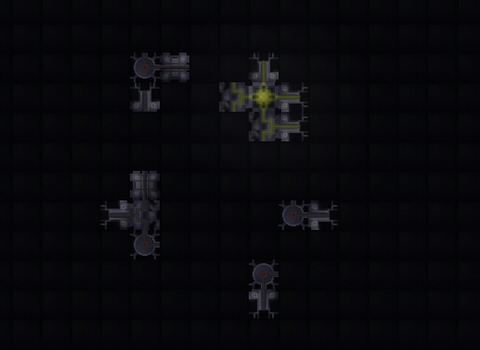

(Nanofactory)

The puzzle game Nanofactory, is no subject to a random generator, but it is related to something remotely similar to coincidence. If you played any adventure of the 1990s, you’ll know the following situation: You solved a particularly absurd riddle (hint: The Secret of Monkey Island) and you need to laugh – in a liberating way. Why liberating? Because nobody could have solved them by purely logical deduction. You try to combine any items of your hopelessly overcrowded inventory without any thinking. Here the coincidence isn’t a part of the game itself, but a part of playing it. Use grog on metal lock. Sure, sure… The irrationality of riddles offers an inexhaustible number of potential possibilities for solutions. That’s how Nanofactory works. The pieces of each puzzle are bigger circuit elements which themselves are splitted into individual, movable elements. The doubled structure of gameplay — on the one hand rotating a piece of the puzzle, on the other hand rotating each individual part — complicates the riddles, makes them absurd. You will reach a point where you just click and flip parts around for minutes. Somewhere along these desperate acts, the solution generously reveals itself to you. By the random rotation of one element, the greater pattern becomes visible. A moment of enlightenment.

No Country for Coincidence

(Real War)

There seem to be a few genres that don’t allow coincidence at all. To me, playing Real War, a war game, was an unbelievable experience. As a nameless soldier, you make your way across the battlefield, talk to your commander, shoot enemies, hopelessly watch your comrades fall victim to cannon shots, and you see a frightened, young soldier struggling with his first kill. War shooters these days, especially the historically oriented ones (think world wars), follow extremely linear paths, as any of these given wars has already happened and is known to anybody who can get his hands on a history book. A quote by Christian Huberts from the German anthology „Welt|Kriegs|Shooter. Computerspiele als realistische Erinnerungsmedien?“ (“World|War|Shooter. Computer games as realistic memory media?”) breaks it down very well:

„Fundamentally, the war ends before it has even begun, we just drive through the most thrilling scenes in a historical setting once again.“

And he’s right. Nevertheless, Real War manages to offer a much more memorable idea of war as unoccasional force, an achievement that your average Call of Duty title could never accomplish, and all simply through its aesthetics.

(Real War)

Farewell

Dear Ludum Dare #23,

at the very beginning, you seemed innocuous and harmless. Testing 150 to 200 games per day – okay, come on, how hard can it be, if the games were programed within 48 or 72 hours? Laughable — at least that’s what I thought.

Turns out it’s not. Just like a little planet, directed by a bacterium-parasite-hybrid, you let laser rays and rockets rain down on me, filled with digital cultural artifacts. At no point you ever stopped to invade more parts of my galaxy. You grew from a tiny world to what’s become my own temporary universe.

There was nothing else but you. You and me. You were a new world, one I wanted to explore. Sure, the human need to eat had to be satisfied here and there, but that wasn’t a problem. Frustrating series of tests were much worse, marathons of dozens of games in a row I didn’t even like one bit. It felt like being attacked by small aliens, or – much worse – by zombie astronauts, not feasting on brains, but on my spare time. But you know what? Sometimes, there was a sparkling stone among them, a rough diamond. My motivation kicked in again. Because I knew that I did it all for the right reason: The love for digital games and their special culture. In the end, I simply wasn’t able to bail on you because of a few little obstacles.

(ONLY US)

With all that said, I hope you never thought I was simply looking down on you, analyzing you. No, I didn’t mean to evaluate you like a mysterious goddess. I didn’t mean to impose those ‘objective standards’ such as graphics, sound, gameplay, story and whatnot. I never ever intended to do that. In the end, all your participants were united by one single thing — and it wasn’t the Tiny World slogan. It was their engagement towards you. Just think about this: With 1.402 submitted games, each developed in 48 hours, a total of almost 67.300 hours has been invested. Invested in you! I would never have been able to evaluate a mass of games as huge as this with conventional and objective rating systems, which is why I tried to pick out all those that meant a lot to me and make them accessible to as many people as possible.

But I kept some special secrets like BEEFWAR, Buggy, Tank and Missile Launcher!!!, Copulous, Cosmicro, Fracuum, Intersection, It’s a Tiny Life…, Miniature Worlds, NaMa Tek, Recluse, Rubiq’s Garden, SAVE YOUR FOLKS!, Singularity, Sirus the Virus, Soul Searchin’, The world of Marceline, Tiny Boss and Tiny Garden of Hope to myself – just for formal reasons, because I thought that I wouldn’t be able to include them. That there were simply too many. Games started to appear too identical. Too many weren’t describable for me. What I then did is pick out five to seven interesting games and bundle them in meta topics like coincidence or relationships. But even that method quickly reached its limitations.

At times, your enormous variety seemed like a plague. An apocalyptical writer’s block hovers over my head just like my own personal Damocles sword. I looked back on my favorite games of the last testing session and tried to establish a connection, but somehow… It wasn’t possible. My relationship to the games was still there, though. I didn’t want to let them go unnoticed.

Your games aren’t perfect, naturally. The majority wouldn’t sell. But is that necessary? I don’t think so. The developers produced them with their concentrated, wild passion. That’s a wonderful thing. It’s a hobby that not only programmers can engage in, but gamers, too. You got it going, dear Ludum Dare #23, I’m certain of it. You provided people with new contacts, ideas and pleasure. It won’t get you big money, neither today nor tomorrow, but you can certainly count on this: Every participant is thankful for you. Even I, in my position as a journalist and gamer, am thankful, because I didn’t only get to know new games and some programmers, but also the team of Superlevel.

I’d also like to thank Dennis and Dom for their help translating this article into English!

(ONLY US)

Dear Ludum Dare #23, you truly were an enrichment to me.

Thank you, xoxo,

Sebastian.

Hidden treasure chest

Atomsmash: Got a place of nostalgically honor, because it’s a Commodore64 disk image!

Cylcubere Origins: An amusing game with the most geometrically varied, sadistic villain of all time. Very nice dubbing!

Desire: On an 8×8 field-island you need to place people according to their personal desires. Very relaxing game to play every now and then.

Discovery: An interesting reenactment in the form of a short point’n’click adventure.

Exposed: An high-end point’n’click adventure about absurd and influenceable evolution.

Finding Yourself: A search for identity and a very, very, very (!) challenging puzzle game at the same time.

Freezen Break: A pun as title, three fruits as protagonists and a good puzzle design. Who can resist that?

It’s a tab: It’s self-explanatory, isn’t it? It’s recommended to play it in Firefox or Chrome.

Microbial: Amazing organic puzzle design — of course in a body cell. It may be a little buggy, but is sure is worth playing.

microrail: Excellent puzzle design with railroad tracks in a micro-organism.

Minilization – Dawn and Fall of Man: Can you prevent the apocalypse by enhancing religion or science?

Mirror Rays: A game with a great gameplay concept, using the reflection of mirrors to offer extraordinary complex riddles.

Moon Base: With the growing Earth in hand, you’re linked to its gravitation field, so that you are forced to factor it in jumping. Very nice gameplay principle.

Naos: For the daily dose of surrealism; may cause headaches.

Nina Nueve: Entertaining 9×9 field puzzle game paired with zeldaesque aesthetic.

Overpopulous: An excellent polished space colonization trip. It’s great fun!

Prince of Leaves: I recommend it just for the unique cute song. Playing, listening, enjoying!

River Runner: A generator for „Just one more try…“-moments. Frustrating good addictiveness.

Tiny Wor ds: Hundreds of tweets to a topic of your choice as a platform! Sweet!

Tinyville Confidential: What would happen if the popular ‘Social Network’-‘game’ cough-cough-cough-Ville portrayed interpersonal relations?

Tondie and Zupe: A tower defense jump’n’punch game, where anything — from towers to the jumping ability and the size of the world — can be upgraded.