Auszug aus “Drachenväter: Die Interviews” – Richard Garriott de Cayeux

Im November 2013 veröffentlichten wir ein (Choose-your-own-)Interview mit den beiden Drachenväter-Initiatoren Thomas Hillenbrand und Konrad Lischka. Ein Jahr später erschien mit “Drachenväter: Die Interviews” der Begleitband zum Buch, der auf gut 160 Seiten eine Sammlung sämtlicher Gesprächstranskripte bereithält. Heute präsentieren wir eine gekürzte Fassung des Interviews mit dem berühmten Rollenspiel-Entwickler Richard Garriott de Cayeux, auch bekannt als Lord British. Viel Freude!

Can you remember when you played your first session of „Dungeons & Dragons“?

Richard Garriott de Cayeux Absolutely! Very clearly. In fact, it was in 1977 in my case. I was attending a summer course at the University of Oklahoma. […] That whole group was already into „Dungeons & Dragons“. That was when I got introduced to it in the original three‑book set and immediately became a fan. […] I had never heard of it before. […] Since it was a seven‑week course where all of us where living there in a dormitory at the university, it was my first significant time away from home. […] It was a very deep initial immersion into fantasy gaming and especially „Dungeons & Dragons“.

Richard Garriott de Cayeux Absolutely! Very clearly. In fact, it was in 1977 in my case. I was attending a summer course at the University of Oklahoma. […] That whole group was already into „Dungeons & Dragons“. That was when I got introduced to it in the original three‑book set and immediately became a fan. […] I had never heard of it before. […] Since it was a seven‑week course where all of us where living there in a dormitory at the university, it was my first significant time away from home. […] It was a very deep initial immersion into fantasy gaming and especially „Dungeons & Dragons“.

What was your character called and what was he or she like?

Garriott My very first character was actually called British. That’s where the nickname Lord British came from. The reason why that was the name of my character, was the students who had arrived there at the school ahead of me, [they would give new students] […] a nickname as they arrived.

In my case, when the students came and knocked at my dorm room door, and I came to the door and they said, ‚Hi“’, and I said, ‚Hello’. They thought hello, or at least the way I said hello, to them sounded foreign, because most of these kids were Southerners with a deep Southern drawl. I grew up next door to NASA, where people’s accents tend to blend away. […] Ever since then, British and Lord British have been the names of the characters that I use, both as a game player and as a game creator.

What was your character like?

Garriott He was a magic user. Right from the get-go, that was the style [of] play that I liked to create and the kind of characters I liked to create, and still do to this day.

You were a Dungeon Master in these first weeks? Or you were just a player?

Garriott In those very first weeks, I started as just a player. But by the end of that seven weeks, I had already started to become more of a Dungeon Master. In fact, I have a story or a belief about those early days of pen&paper gaming, and how it evolved that you may find interesting; which is that if you think about the earliest adopters of „Dungeons & Dragons”, early university, those were the people that it appealed to first, were the people who had the strongest potential passion for it.

In other words, you didn’t even have to be marketed into it. You were immediately drawn to it, without regard to having to hear about any marketing or advertising, by the time it was popular. Those earliest adopters, people such as myself, very commonly were very good interactive story tellers.

My memories of the first three of four years of playing „Dungeons & Dragons” was that many of the players were also extremely good interactive storytellers. I think that is part of the self‑selection process of being one of the very early adopters. As the game grew in popularity, you found that it slowly became true that the majority of players were not very good Dungeon Masters. […] To that end, it’s interesting that after three to five years of people playing „Dungeons & Dragons”, the games that I would go see being played, had often devolved into arguments about rules versus true interactive story telling. […]

To me, that happened because we ran out of good story tellers. That same sentiment carries over into online gaming today. The real issue is storytelling and true role playing. The fact is that there are lots of people who love to play role playing games. Many people even attempt making them, but very few [are] high quality interactive story tellers to craft great stories.

Did „Dungeon and Dragons“ in the early days grow out of table-top wargaming? Did it feel similar back then, or was it something completely different from the very beginning?

Garriott Yes exactly! In fact, if you think about people who play with Miniatures, that wasn’t very often. […] [I]f you look at the beginnings of „Dungeons & Dragons”, it sort of grew out of Miniatures. If you think of the very early supplement called „Chainmail“, it really was a Miniatures rules set for how to use little fantasy characters, and use them the same way that people were already doing with „Toy Soldiers” and other military campaign simulations.

They really were down to numbers and measuring distances, angles and cover and trying to accurately simulate a military campaign. D&D sort of grew out of that into interactive story telling. In my mind, some of its best years really were those first five or ten years – where the rules were irrelevant and interactive story telling ruled.

Was the „Society for Creative Anachronism“ similar to pen&paper role playing in the early years?

Garriott Yes. In fact, if you think about the SCA, that’s a group of historical re-enactors. But [they] also take a great artistic license as to the role playing you do live or out camping for the weekend. There was a reasonable overlap. Many SCA participants were D&D players, but by no means all. […] Compared to the general populace, where only maybe one out of 100 people even knew what „Dungeons & Dragons“ was. Maybe one out of three people in the SCA was also a „Dungeons & Dragons“ player. It was a heavy overlap, but no means a majority.

If you look at the „Ultima“ series, many of the early „Ultima“ characters were many of my college friends who were also in the SCA. In fact, right across from the office of me right now there’s a map being built where some of the phrases or dim jokes, in this particular case, about ducks that were spawned by my SCA college friends that have made it into all of my games, including the new game I’m working on now. The SCA, and my friends in the SCA, have been very influential in the development of online games after „Dungeons & Dragons“.

When did you get in and how did you get into the SCA?

Garriott That came about right as I entered college. I was at the university co‑op, and a place where they had an arcade hall and a restaurant, and some other members of the SCA were going to the demonstration there, in one of the big open rooms, and as somebody who was already into „Dungeons & Dragons”, that of course, appeared to be right up my alley, so I signed up immediately.

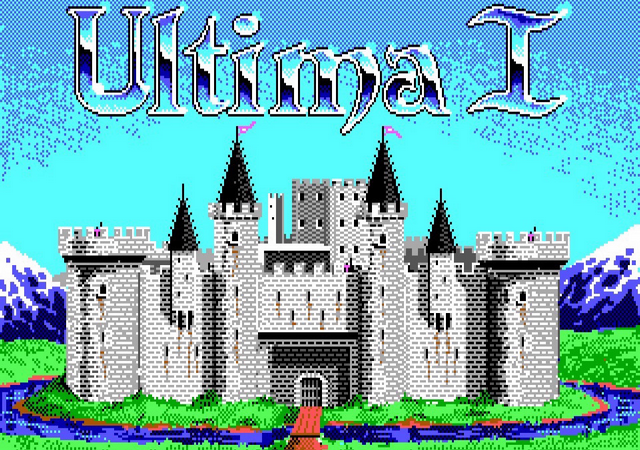

[…] [„The Lord of the Rings”] influenced the first „Ultimas“. You had hobbits as characters …

Garriott I’m sure it was probably a Tolkien influence. If you look at the „Ultima“ I to III, they really were pulling from all the things I thought were cool in life. This was when I was in high school and college that I wrote these. Even the cloth maps and moon gates from „Ultima“ really came from the movie „Time Bandits”. There were lightsabers and blasters and landspeeders and such in the first few „Ultimas“ from, of course, „Star Wars”. There were tons of influences from „Lord of the Rings”. All my SCA friends became part of the game. The basic was an amalgamation of all the things I found inspirational around me, during those times. It wasn’t really until „Ultima” IV that I sat down and said: ‚I want to craft my own world’. […]

[…] If you can describe it, how does „Dungeons & Dragons“ and role‑playing at the SCA influence you as a designer? How did this get into the kind of game you try to make? What elements did you want to take from these games to the first games you created for the computer?

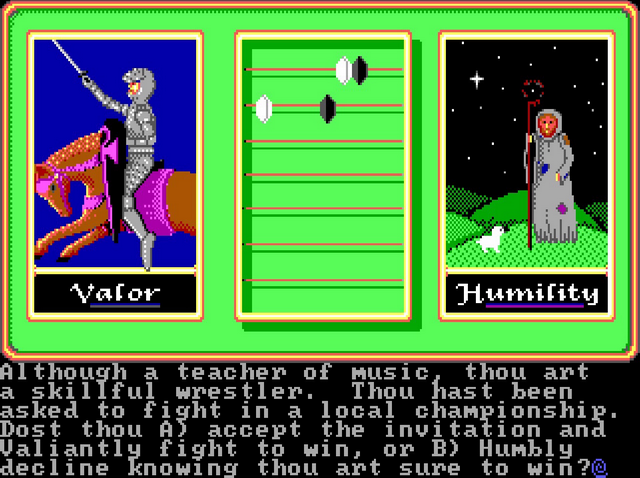

Garriott What’s interesting, the influence of D&D and SCA really, on the early computer games I created, was definitely that feeling of a true interactive story. The „Ultima“ series was not by any means the only role‑playing game being made at the time, there were many others: „Wizardry“, „Bard’s Tale“, „Might and Magic“.

While a lot of my competitors were focusing really on combat systems, and so they were really focusing on the numerical aspects of the challenge-and-reward cycle – which by the way, is very important to having a good game: A properly‑tuned challenge-and-reward cycle can take a game from being challenging and interesting to being either boring or impossible. Those games often did that very well – often better than I did in the „Ultima“ series. What the „Ultima“ series did well that really drew from D&D and the SCA, was to try to really figure out a way to do honestly interactive storytelling, where instead of just going through a linear story in a fantasy world, that you are on rails that you can’t or shouldn’t deviate from, just like a good pen&paper session, where the Dungeon Master has some loose ideas as to where he hopes the people will go, that in pen&paper you’re trying to invent just ahead of the players in real‑time. We try to do something similar in a computer game.

While a lot of my competitors were focusing really on combat systems, and so they were really focusing on the numerical aspects of the challenge-and-reward cycle – which by the way, is very important to having a good game: A properly‑tuned challenge-and-reward cycle can take a game from being challenging and interesting to being either boring or impossible. Those games often did that very well – often better than I did in the „Ultima“ series. What the „Ultima“ series did well that really drew from D&D and the SCA, was to try to really figure out a way to do honestly interactive storytelling, where instead of just going through a linear story in a fantasy world, that you are on rails that you can’t or shouldn’t deviate from, just like a good pen&paper session, where the Dungeon Master has some loose ideas as to where he hopes the people will go, that in pen&paper you’re trying to invent just ahead of the players in real‑time. We try to do something similar in a computer game.

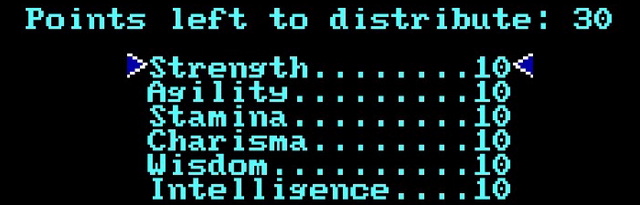

Speaking of mechanisms: Elements like experience points, levels, hit points, weapons with +1 or +2 bonuses and so on – these today universal concepts in computer games come from pen&paper role‑playing games? Or do you know any other possible source?

Garriott No, they definitely come from pen&paper. Unquestionably. What I find funny about a lot of early and even still [contemporary] computer games, is computer games commonly will include all of the attributes that come from people’s favorite pen&paper games; Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Charisma.

And what I really find funny is even in [the] pen&paper area I find a lot of the attributes of a character to be a waste of a data field on a piece of paper. Charisma, for example. If you have a number, that number needs to be utilized in a lot of circumstances before the number is actually relevant. And […] it’s close to never that I see people in a pen&paper session test against their Charisma. […]

[S]o I tend to be a minimalist when it comes to attributes in a game. So I say: ‚Look, least I can think of thousand occasions running tests on that attribute, don’t bother making unique attributes, just choose one of the other attributes that’s similar’.

I always laugh when I see someone creating computer games with a lot of statistics and a things like Charisma, because I know very well that charisma was probably never tested in a period of game‑play. They are putting it in because pen&paper games had it in.

How has the role-playing aspect developed over time in computer games? Has it become more or less important if you compare it with the late nineties, early eighties?

Garriott That’s [an] interesting question. There seems to be two styles of evolution. One where the character becomes less important, which is really the designers have set out the path to follow, and what character you do it with doesn’t really matter, in fact there is so little variation in it that hardly even matters. […]

There is [a] second school of thought which myself and my team are really focused on which is making sure that the choices you make and the character that you create are really relevant and impact full to [the] experience you have [with] the game. But I think it is less common than the first route, which is ‚follow the leader’. I think […] a lot of role playing games are very quite linear.

How does interactive storytelling change through the rise of multiplayer online role playing games?

Garriott If you are playing a solo game where each of you who have bought a game are supposed to be the great hero that saves the world and kills the bad guy, you don’t mind that your neighbor who has bought and is playing the same game in his house believes they’re the hero that saves the world and kills the bad guy.

But if you’re in a shared experience, suddenly the fact that someone is standing next to you in the world, who also believes they are the one great hero and they’re the one person who killed the great bad guy, kind of loses its luster. And so doing the storytelling in a multiplayer environment is considerably harder than doing it in a solo player environment.

And in fact, I would still say that storytelling in a multiplayer setting is relatively speaking […] infancy compared to […] solo player games. And by the way, we are not very good at it […] as an industry [to] get in solo players, and it’s considerably harder in multiplayer games.

But in MMORPG you sometimes see people doing things the game master did in the old days. Guilds with own stories and backgrounds, setting their own goals and internal rules. But this has never developed into something like you meet with your certain friends and you play your own game. The background story still is always provided by the producer in MMORPGs.

Garriott That’s correct but also, just like I said, if anything becomes popular like a massive multiplayer game, the more people are in it, the less qualified the majority of those people are to add interesting concept.

So while the good news is on MMO, an open sand box world allows people to find and create kind of their own communities, their own stories, and their own adventures, most of those people are not good game masters and don’t have the tools even to try to game master for their friends within that virtual environment.

And so the labor, the challenge, still lays at the feet of developers to create not just the opportunities for but the framework and story threads and push to get the players to engage. They still fundamentally are driven by the games developers, although you want as much as possible let the players evolve that and push that on their own as well.

That is so hard to interactive storytelling as a producer or game master, and that is the reason why pen&paper role playing never became main stream phenomenon?

Garriott The short answer is yes to that. If you think about the rules for example of „Monopoly“, they’re very consistent, they’re very few. And so mom, dad and a kids can sit around the table and play. So „Monopoly“, which is actually pretty complex for a board game, is capable of being broadly popular to families.

On the other hand looking at „Dungeons & Dragons“, even in its simplest form, the complexity of it is radically higher than „Monopoly“, and it requires a level of abstraction and personal creativity that goes far beyond „Monopoly“. So foundationally, it’s much more difficult to envision D&D where somebody has to choose to be the game master, somebody has to be creative enough to create compelling content for everyone else – when there are so few people who really are creative enough to create great compelling content. It’s no surprises that most families don’t have an interactive story teller in their family.

Why do you think TSR has failed as a company?

Garriott Well, if you think of evolution of any piece of intellectual property, it has to grow and evolve with the times and the audience and technology potentially around it.

TSR has, in varying years, done phenomenally good work that I think resonated well with generic public and often gone through decade or so, time where either did not have the eye around the ball or added levels of the complexity or detail that didn’t really help for growth of that property.

But I don’t think that TSR did it any better or worse [than] almost any other company managing a mega property like that, it’s […] very difficult. I think they managed well and I don’t think they did a particularly [bad job]. They did as well as they could with what they had, I think.

But it couldn’t grow much?

Garriott It definitely could be „Monopoly“, if you know what I mean. At least in that form of reincarnation it could have become Monopoly.

There are other people that have tried to create role-playing games that were even further simplified, that might have been more successful [with a] broader audience: […] games where you might put out little tiles of dungeon that you have to arrange on a table top with super-simplified rules to make a dungeon crawling game that could been seen [complex] as „Monopoly”. But then those are not interactive storytelling.

I so think that the blessing and the curse of interactive storytelling is that interactive storytelling when done well is phenomenally impact‑full, but requires at least one member of the group to be [an] interactive storyteller of which there are not as many.

What future do you see for pen&paper role-playing?

Garriott I think that these simulation of pen&paper role‑playing that we do on computers is far from perfect. I actually think that a phenomenally good interactive story being told around the dinner table by a well‑qualified game master, remains a pinnacle experience. It was just a rare experience, a hard to share experience.

Das Interview ist ein gekürzter Auszug aus „Drachenväter – die Interviews“ (als E-Book für 2,99 Euro erhältlich, die gedruckte Version kann für 15,99 Euro erworben werden). Das Buch stellt eine Sammlung der vollständigen Gesprächstranskripte dar, die im Laufe der Arbeit an dem Buch „Drachenväter“ entstanden sind.

Weitere Informationen gewünscht? Dann lohnt sich ein Besuch auf der Drachenväter-Seite.